The year 2014 is most certainly the Year of Galileo.

3 September 2014

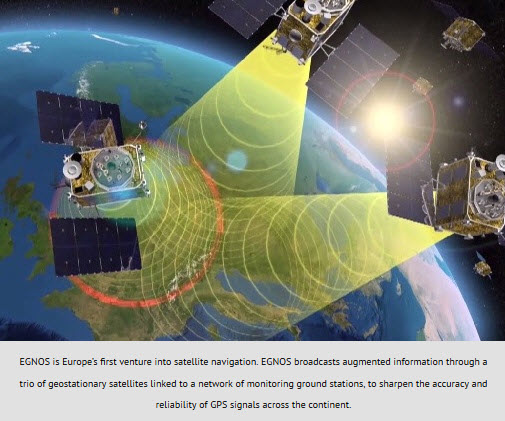

After rising up from near elimination in 2008 due to much confusion about how to fund it, the European Union, that same year, decided to allocate 3.4 billion euros to fund the ground infrastructure and the initial satellites. Unlike the U.S. GPS and Russian GLONASS systems, Galileo is civilian-funded as opposed to being funded primarily from defense budgets, which makes it politically much more difficult to gain funding. But, they did it.

That was six years ago.

Since then, ground infrastructure has been designed and built. Six test satellites have been designed, built and successfully launched into orbit. In early 2013, the first position fix using only Galileo satellites was achieved. With all the necessary test satellites launched and systems tested, the anticipation of FOC (Full Operational Capability) satellite launches has been high, because it would signal the rapid deployment of the Galileo navigation system that would so complement GPS and so benefit the high-precision GNSS user community.

Soyuz Flight VS09, carrying Europe's fifth and sixth Galileo satellites, lifts off from Europe's Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana.

That moment arrived last month, on August 22, with the launch of the first two Galileo FOC satellites. The significance of the first FOC launch is that it would trigger an aggressive launch schedule comprised of one launch every three months, at two satellites per launch — equaling eight satellites launched per year. With four test satellites already in orbit being converted to operational satellites, one can envision 16 Galileo satellites in orbit by the end of next year. While not a complete constellation at that point, it would offer plenty of upside — worldwide I might add, as I’ve written about in the past — by adding more satellites in view and accelerating the adoption of the new L5 signal, which is also supported by GPS.

Between Europe deploying Galileo and China deploying its BDS (BeiDou) system, the world of high-precision GNSS is going to change a lot in the next couple of years. There will be more receiver choices at much lower prices for RTK receivers.

But, the satellite navigation business is not a forgiving one. The devil is in the details, and the number of details has got to be overwhelming. Consequently, there have been many casualties.

The Russians have taken their lumps, losing a total of seven GLONASS satellites to faulty rocket launches in just the past four years.

In 2009, the U.S. placed into orbit a GPS satellite, SVN-49, that never has been set healthy, rendering it a “$100M test satellite.”

Now, the Europeans have joined the club.

The “pucker factor” during the satellite launches is always high, so on August 22, when two Galileo satellites mounted on a Russian Soyuz rocket at the Arianespace launch pad in French Guiana were pushed up into space, there must have been a sigh of relief that the launch seemed to go smoothly. Even I was excited, Tweeting “#Galileo Launch Successful, Satellites Deployed. Booyah!”, shortly after the launch.

However, looks can be deceiving.

It turns out that somehow, some way, the two Galileo satellites, after years of planning, were inserted into the wrong orbits.

The liftoff and first part of the mission proceeded nominally, reports Arianespace, leading to release of the satellites according to the planned timetable, and reception of signals from the satellites. However, the targeted orbit was circular, inclined at 55 degrees with a semi major axis of 29,900 kilometers. The satellites are now in an elliptical orbit, with excentricity of 0.23, a semi major axis of 26,200 km and inclined at 49.8 degrees.

With navigation satellites, we’ve seen disastrous launch failures and defective satellites placed in orbit, but I can’t recall ever hearing about navigation satellites being inserted into the wrong orbits. It’s difficult not wonder how such a seemingly simple error could occur, yet sympathize with the Galileo program managers given the complexity of the task, but also appreciate the consistency and reliability of GPS satellite deployments.

Booyah!”, shortly after the launch.

However, looks can be deceiving.

It turns out that somehow, some way, the two Galileo satellites, after years of planning, were inserted into the wrong orbits.

The liftoff and first part of the mission proceeded nominally, reports Arianespace, leading to release of the satellites according to the planned timetable, and reception of signals from the satellites. However, the targeted orbit was circular, inclined at 55 degrees with a semi major axis of 29,900 kilometers. The satellites are now in an elliptical orbit, with excentricity of 0.23, a semi major axis of 26,200 km and inclined at 49.8 degrees.

With navigation satellites, we’ve seen disastrous launch failures and defective satellites placed in orbit, but I can’t recall ever hearing about navigation satellites being inserted into the wrong orbits. It’s difficult not wonder how such a seemingly simple error could occur, yet sympathize with the Galileo program managers given the complexity of the task, but also appreciate the consistency and reliability of GPS satellite deployments.

Galileo satellites fastened to upper stage.

The Russians quickly commented on the satellite deployment anomaly since it was a Russian Soyuz rocket launcher, speculating that it was a software bug. The Russian newspaper Izvestia quoted an unnamed source from the Russian Space Agency Roscosmos that “the failure of the European Union’s Galileo satellites to reach their intended orbital position was likely caused by software errors in the Fregat-MT rocket’s upper stage.”

It’s too early to say if the Galileo satellites will ever become serviceable. The Monday following the launch, an independent inquiry commission was formed to “establish the circumstances of the anomaly, to identify the root causes and associated aggravating factors, and make recommendations to correct the identified defect and to allow for a safe return to flight for all Soyuz launches from the Guiana Space Center (CSG).”

Despite being in the wrong orbit, it seems that the satellites are under full control and ready to proceed with the next stage of the launch and early operations phase activities. However, one option is not using on-board fuel to propel the satellites into a higher orbit.

This subject will certainly be a hot topic at the Institute of Navigation (ION) GNSS conference being held next week in Tampa, Florida. A full staff of GPS World editors and administration folks will be attending, including yours truly. It’s the premiere GNSS technical event of the year, so I’m sure there will be plenty of scientists and program managers commenting and speculating on the future of these two satellites.

If you’d like the latest news on this and other GNSS-related subjects during the conference next week, follow me on Twitter at https://twitter.com/GPSGIS_Eric. There are lots of interesting subjects at the ION GNSS+ conference. Take a look at the conference agenda here. I’ll be attending many of the presentations related to high-precision GNSS and report to you in next month’s newsletter. To give you a flavor, following are some of the presentations that I’m going to try to attend.

- The Triple-frequency Multi-system RTK Engine for Challenging Environments

- Mobile Mapping Using Smartphone

- Analysis of Using Smartphones for Indoor Mobile Mapping

- GPS Program update

- Galileo Program Update

- Glonass Program update

- BDS Program update

- GLONASS Only and BeiDou Only RTK Positioning

- Comparing Multi-constellation and Multi-frequency Based on GPS/Beidou RTK Positioning

- Combined GPS+BDS+Galileo+QZSS for long single-baseline RTK positioning

- Real-time PPP with Galileo, Paving the Way to European High Accuracy Positioning

- High-Precision GNSS — What will it Look Like in 2020?

Source

That was six years ago.

Since then, ground infrastructure has been designed and built. Six test satellites have been designed, built and successfully launched into orbit. In early 2013, the first position fix using only Galileo satellites was achieved. With all the necessary test satellites launched and systems tested, the anticipation of FOC (Full Operational Capability) satellite launches has been high, because it would signal the rapid deployment of the Galileo navigation system that would so complement GPS and so benefit the high-precision GNSS user community.

Soyuz Flight VS09, carrying Europe's fifth and sixth Galileo satellites, lifts off from Europe's Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana.

That moment arrived last month, on August 22, with the launch of the first two Galileo FOC satellites. The significance of the first FOC launch is that it would trigger an aggressive launch schedule comprised of one launch every three months, at two satellites per launch — equaling eight satellites launched per year. With four test satellites already in orbit being converted to operational satellites, one can envision 16 Galileo satellites in orbit by the end of next year. While not a complete constellation at that point, it would offer plenty of upside — worldwide I might add, as I’ve written about in the past — by adding more satellites in view and accelerating the adoption of the new L5 signal, which is also supported by GPS.

Between Europe deploying Galileo and China deploying its BDS (BeiDou) system, the world of high-precision GNSS is going to change a lot in the next couple of years. There will be more receiver choices at much lower prices for RTK receivers.

But, the satellite navigation business is not a forgiving one. The devil is in the details, and the number of details has got to be overwhelming. Consequently, there have been many casualties.

The Russians have taken their lumps, losing a total of seven GLONASS satellites to faulty rocket launches in just the past four years.

In 2009, the U.S. placed into orbit a GPS satellite, SVN-49, that never has been set healthy, rendering it a “$100M test satellite.”

Now, the Europeans have joined the club.

The “pucker factor” during the satellite launches is always high, so on August 22, when two Galileo satellites mounted on a Russian Soyuz rocket at the Arianespace launch pad in French Guiana were pushed up into space, there must have been a sigh of relief that the launch seemed to go smoothly. Even I was excited, Tweeting “#Galileo Launch Successful, Satellites Deployed. Booyah!”, shortly after the launch.

However, looks can be deceiving.

It turns out that somehow, some way, the two Galileo satellites, after years of planning, were inserted into the wrong orbits.

The liftoff and first part of the mission proceeded nominally, reports Arianespace, leading to release of the satellites according to the planned timetable, and reception of signals from the satellites. However, the targeted orbit was circular, inclined at 55 degrees with a semi major axis of 29,900 kilometers. The satellites are now in an elliptical orbit, with excentricity of 0.23, a semi major axis of 26,200 km and inclined at 49.8 degrees.

With navigation satellites, we’ve seen disastrous launch failures and defective satellites placed in orbit, but I can’t recall ever hearing about navigation satellites being inserted into the wrong orbits. It’s difficult not wonder how such a seemingly simple error could occur, yet sympathize with the Galileo program managers given the complexity of the task, but also appreciate the consistency and reliability of GPS satellite deployments.

Booyah!”, shortly after the launch.

However, looks can be deceiving.

It turns out that somehow, some way, the two Galileo satellites, after years of planning, were inserted into the wrong orbits.

The liftoff and first part of the mission proceeded nominally, reports Arianespace, leading to release of the satellites according to the planned timetable, and reception of signals from the satellites. However, the targeted orbit was circular, inclined at 55 degrees with a semi major axis of 29,900 kilometers. The satellites are now in an elliptical orbit, with excentricity of 0.23, a semi major axis of 26,200 km and inclined at 49.8 degrees.

With navigation satellites, we’ve seen disastrous launch failures and defective satellites placed in orbit, but I can’t recall ever hearing about navigation satellites being inserted into the wrong orbits. It’s difficult not wonder how such a seemingly simple error could occur, yet sympathize with the Galileo program managers given the complexity of the task, but also appreciate the consistency and reliability of GPS satellite deployments.

Galileo satellites fastened to upper stage.

The Russians quickly commented on the satellite deployment anomaly since it was a Russian Soyuz rocket launcher, speculating that it was a software bug. The Russian newspaper Izvestia quoted an unnamed source from the Russian Space Agency Roscosmos that “the failure of the European Union’s Galileo satellites to reach their intended orbital position was likely caused by software errors in the Fregat-MT rocket’s upper stage.”

It’s too early to say if the Galileo satellites will ever become serviceable. The Monday following the launch, an independent inquiry commission was formed to “establish the circumstances of the anomaly, to identify the root causes and associated aggravating factors, and make recommendations to correct the identified defect and to allow for a safe return to flight for all Soyuz launches from the Guiana Space Center (CSG).”

Despite being in the wrong orbit, it seems that the satellites are under full control and ready to proceed with the next stage of the launch and early operations phase activities. However, one option is not using on-board fuel to propel the satellites into a higher orbit.

This subject will certainly be a hot topic at the Institute of Navigation (ION) GNSS conference being held next week in Tampa, Florida. A full staff of GPS World editors and administration folks will be attending, including yours truly. It’s the premiere GNSS technical event of the year, so I’m sure there will be plenty of scientists and program managers commenting and speculating on the future of these two satellites.

If you’d like the latest news on this and other GNSS-related subjects during the conference next week, follow me on Twitter at https://twitter.com/GPSGIS_Eric. There are lots of interesting subjects at the ION GNSS+ conference. Take a look at the conference agenda here. I’ll be attending many of the presentations related to high-precision GNSS and report to you in next month’s newsletter. To give you a flavor, following are some of the presentations that I’m going to try to attend.

- The Triple-frequency Multi-system RTK Engine for Challenging Environments

- Mobile Mapping Using Smartphone

- Analysis of Using Smartphones for Indoor Mobile Mapping

- GPS Program update

- Galileo Program Update

- Glonass Program update

- BDS Program update

- GLONASS Only and BeiDou Only RTK Positioning

- Comparing Multi-constellation and Multi-frequency Based on GPS/Beidou RTK Positioning

- Combined GPS+BDS+Galileo+QZSS for long single-baseline RTK positioning

- Real-time PPP with Galileo, Paving the Way to European High Accuracy Positioning

- High-Precision GNSS — What will it Look Like in 2020?

Source